Showing posts with label Chekhov. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Chekhov. Show all posts

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Reading Like A Writer: Story Structure

Photo: The Golden Gate Bridge, in an aerial view, from the bridge's Wikipedia page. Click it; it's a great pic.

I've been trying to read books lately with a writer's eye, so that I could learn what makes successful (defined here as published; maybe also as respected and/or successful writer) writers write successful things. I've had (extremely) modest success recently, and I've been trying to learn why some pieces have sold and why some haven't. Here's what I've come up with recently:

--Stories sell better if they have a structure, and not just a "this happens, then this happens" kind of feel. Readers can feel the flow of the structure; they're pulled along by it. So the story, the characters, the setting--all of that is important, but the flow of the structure is like a double-pull with all of those things. Stories that are just a series of events don't have that flow, and so the reader feels disjointed right away, even if the characters and the plot and that stuff are solid. No structure, no flow, no pull.

--The structure we've all learned in high school--the Shakespearean Plot Triangle--is not the only structure to use. Some stories just won't fit to that form, especially if there's no solid climax in the middle of the piece, or a clear finish for the resolution. And not if the story doesn't break cleanly into five or so different parts. There may not be a clear rise to the climax, or fall from it to the end, especially if the end isn't tragic or definitive. For example, if the ending is more in the Chekhov vein, where you're dropped into the lives of the characters, and they're not done at the end--or even if there really isn't an established end, then the five-part plot triangle won't fit. And you can't make a story fit a structure that it just isn't made to fit. You can't force a structure upon a story.

--A three-part story structure that works for me lately--that I think might work for one of my novel manuscripts that I'd been sort of forcing a five-part structure on--is called the Suspension Bridge structure. It differs greatly from the plot triangle because there's not much building up, nor falling away from, though the ending is usually pretty solid like it would be at the end of the plot triangle.

Picture an actual suspension bridge. It starts at the land's edge, and the bridge's cables swing up to the first apex. This is the build-up of the character, his traits, and his flaws, and the climax, if you will, of the peak there is when he gets something that he wants, that might better his plight. This thing must change the character in a major way--or it has to at least offer the possibility. Usually this involves a change in the character himself; it sets up the character vs. self conflict, though there must be many other conflicts to come. Then the bridge cables drop. And it's a long, long drop, and somewhere there is a rock-bottom, in which the character is threatened with the possibility of going back to where he started, if not worse. This is also where all of the conflicts are established for that thing that he wants and here's where the antagonists are established. This is also where the big reveal of a big conflict happens, something the protagonist might not even know. But then he does. Then the next upswing starts; he overcomes those conflicts somehow and succeeds in some way by the apex of that next upswing. There was such a huge crash before so then, when he succeeds for the next upswing, that apex of that upswing has to be a major victory, much more so than the previous one, and it sort of wraps up the whole story. The space between these two apexes is the vast majority of the story. The last descent is not necessarily a downswing--it just has to establish the normalcy again of this character's new life as the bridge's cables connect to the land again. The dust has settled, and the character's life is a bit more clear, usually in a good way. The ramifications of the victories and successes are shown, and the character again carries on with his life, and both you and the character feel it'll be better.

This structure is much more open for characterization, and is an especially good structure to use if one of the main conflicts is character vs. self. The best example I've noticed recently of this suspension bridge structure is the movie The Verdict, which I mentioned in the recent blog about signs you're growing old: it's the movie I sought, made in 1982, and I sought it because I needed to see it again, because it suddenly hit me, purely from memory, that it was the epitome of the suspension bridge structure.

I'll explain how and why in a blog entry to come.

Monday, February 27, 2012

The Best American Mystery Short Stories

photo: cover of the book from its Amazon page

A few comments about the stories I've read so far in The Best Mystery Short Stories--1998 (edited by Sue Grafton). Though of course the collection is old, stories are stories, and good writing is timeless. You couldn't do much better, for example, than some of Chekhov's short stories; writers like Alice Munro and others are still obviously indebted to him. The hope here is that you'll check out the other works of the writers positively mentioned below. Most of them are still pounding the keys...

Child Support, by David Ballard

Not overly impressive. Generic story about a guy, who you don't like, wheeling his baby around in a carriage, and walking his dog, at the same time, and grousing about it. He's being divorced; the language and tone he uses to think about his ex-wife and baby make you dislike him immensely. That is, of course, the idea. So these tough-looking guys straight out of every bad (and good) film of its type approaches him. He thinks they're from this guy he owes a lot of money to (he's a gambler, too, of course). They say that they'll give him riches if he can make his dog catch a frisbee eight times. The dog is super-awesome and by far the best character of the story. If not, they threaten to kill him, take the baby for immoral purposes, or both. (So you could argue he takes the wager to save the baby's life, which defeats the entire purpose of the story, and is clearly overlooked by Ballard.) The dog drops the eighth toss, after seven predictably tough and awesome catches. Just when he thinks he'll be plugged and his baby stolen, the guy whips out a card, introduces himself as his ex-wife's lawyer, tells him they have it all on film--him taking the wager--and then his ex-wife gets out of the car at the curb. The guy hands over custody of the baby and the dog to the wife. The story reads as bad as it sounds. The writing is so pedestrian that I constantly felt I could do better. Hard to believe this one was chosen to start off the book, but a quick look now at the Table of Contents shows that they listed them in alphabetical order, by the author's last name. Hard to believe this was one of the best mystery stories of 1998, or of any year.

Swear Not By the Moon, by Scott Bartels

This was a very edgy, harsh and effective short story about drug addiction, crime, and the depths that an addict will go to just get away. Very desperate story, desperately written. It all goes to hell at the end, of course, and the crime he commits isn't the one he was supposed to commit (though neither one is better), and you get the impression that his end won't be a good one, and it'll be soon. Well-written and memorable. There's no mention in the story, by the way, of the title, or the title's source, which I know you know is Romeo and Juliet. (At the balcony scene, she tells him not to swear his love on the moon, the inconstant moon, because it's face changes every night.)

Keller on the Spot, by Lawrence Block

Passable short story, very readable, though not extremely memorable. A hitman is sent on a job, but saves the life of the grandson of the target. The guy thanks him, and the hitman grows to like him, so he doesn't want to kill him. He tries to get out of it, but can't, unless he walks away--at which point they'll just send another hitman to do the job. But, turns out, the target ordered his own hit--he's the customer. He has cancer, so he wants to get shot because he couldn't kill himself. But the target knows the hitman was sent to do it, and he doesn't want to get killed anymore, at least not by that guy. The waiting's been killing him, knowing it could be any second. The anxiety just wore him down. So he cancels his own hit, and still pays in full, so nobody's going to shoot him after all. He says goodbye to the hitman; they've become good friends. At their goodbyes, it's obvious that the target is still in a lot of pain from the cancer, so the hitman will hang around the city for a few days, until the guy gets calm and relaxed again--but still in great pain--and then the hitman will put him out of his misery. Well done, very readable. Fans of the genre will know Block's name.

The Man Next Door, by Mary Higgins Clark

Hate to say it, but this is really bad, one terrible cliche after another. A serial killer with a mommy complex lives next door to attractive younger woman who's too trustful and friendly to the weird neighbor. He takes down his cinderblocks in his basement and enters hers that way, which is how he gets into her house unseen, and injects her with something so he can bring her to his basement, where he makes her read him children's books, and he responds like an adult infant. Meanwhile, the boyfriend just knows there's something wrong, and he investigates. Turns out, the killer also has OCD issues, to the extent that he tidied up the woman's house after he'd kidnapped her. And she's a lovable slob, so everyone knows someone's been in the house. And the guy next door has become infamous for his manicured lawn, and pristinely-pinned curtains. The boyfriend gets to the basement just in the knick of time...Ugh! So bad, you compulsively keep reading, mesmerized by how awful it is. Hopefully her novels are better than this. Hard to believe this writer is a famous millionaire.

This Is A Voice from Your Past, by Merrill Joan Gerber

Very, very well-written story, very touching and memorable. A woman with a husband, kid, and another on the way gets a call from a college lover, asking for a favor. As the story says, it's a call we all get, in one fashion or another, and we all dread it when we get it. This guy had been the gifted writer of the college class they shared, a sure thing. The professors and students all thought so. But he drinks, and drifts...and then calls. He and the narrator meet up after the second time he called, thirty years after the other call. She's a published author by then herself, making a reasonable but not rich living, and she's a college professor as well, teaching creative writing. He's in AA, destitute like last time, but in town, he says, living there because she lives there. She doesn't want to see him, afraid of the feelings and memories he turns up--and churns up, as he's irascible and unreliable. She's too nice to ignore him, so she invites him over a few days later, when she's having a big family and friend barbecue. He looks really bad, and pathetic, and by the time he leaves, he's eaten a piggish amount of food, he's been given all of the tons of leftovers, and he even walks off with the narrator's old but cherished typewriter, which she still uses. Soon she's gotten him a place to stay, and he attends her class...only to leave with a much younger and naive female student, who naively lets him borrow her car, which he takes to the racetrack and to bars, with predictable results. And he leaves with the typewriter after he drops the car off at the girl's place, its tank empty. Much later, the typewriter turns up at the guy's wheelchair-bound brother's place, because the brother finally told him to get lost and stop mooching off of him...Finally, the third call comes. He's yelling, screaming, angry, obviously on a bender, and tells her that he's stopping by right away. Days, weeks, months go by--and the narrator cringes every time the phone rings. This is a well-written story about enabling the needy, which we've all done, and about that someone we all know who we're afraid will call and disrupt our lives, yet we're almost powerless to do anything about it.

Full disclosure: On a whim, I came across Ms. Gerber's website, on LinkedIn and via the university at which she teaches. I sent her one very short complimentary email, which she was kind enough to respond to. She wrote that I wrote like a writer, which is one of the better compliments I've gotten about my writing (I think).

More to come...Check these writers out. They have other books and stories out there.

P.S.--This book is available at Amazon for $88.00 because it has four autographs--one from Ms. Gerber, Lawrence Block, Mary Higgins Clark and Donald Westlake, who's story will be covered in a later post.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

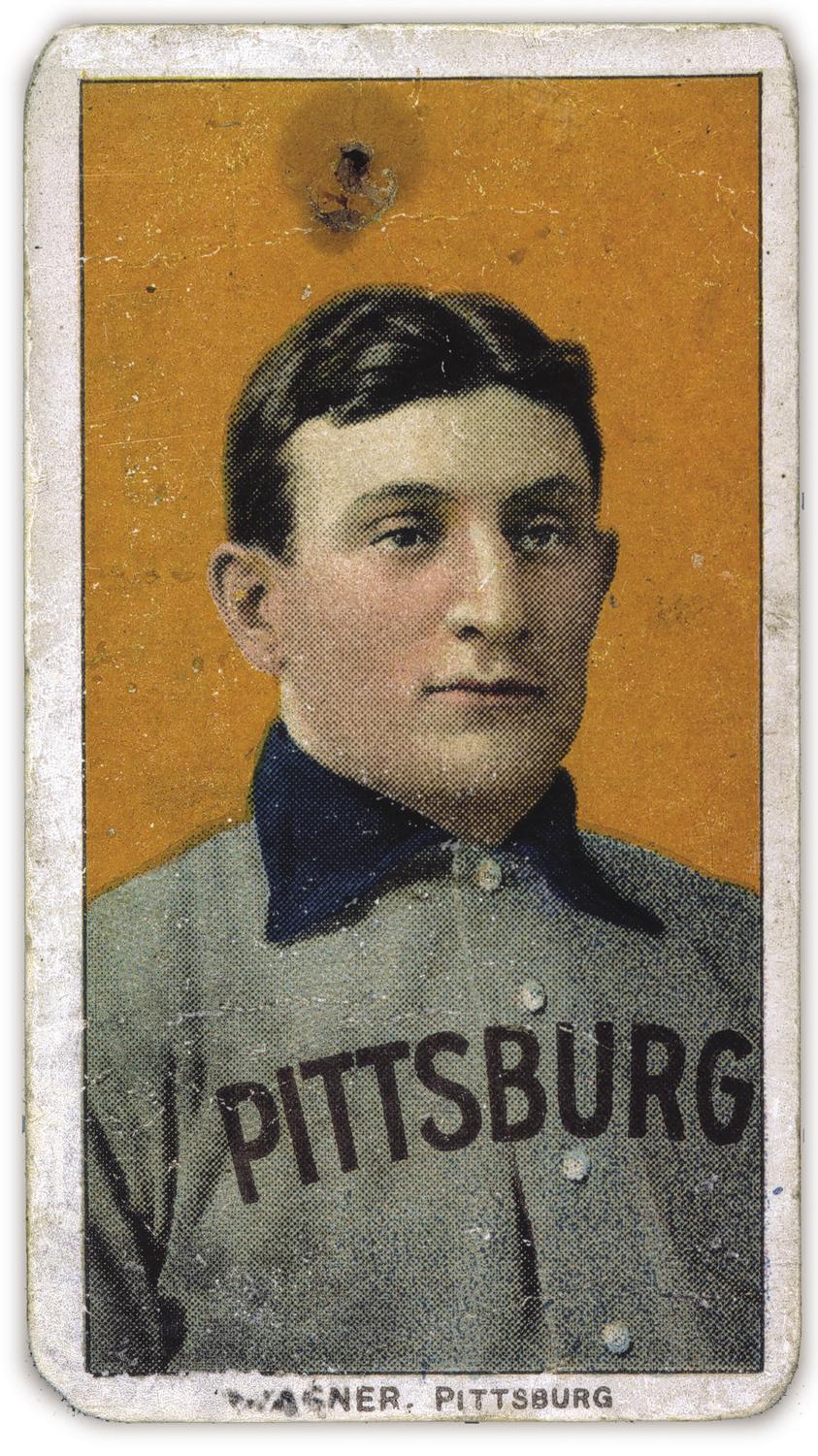

A Different Library and the T206

Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

I'm sitting here now at a different library than the one I'm used to. This one is practically across the street from Borders, so I can quickly go there to work on my paper when the library closes. I am enough of a literary freak to really appreciate libraries, and different places to write in general. The best I've ever been in is the New York Public Library in Manhattan, which is beautiful beyond description and even owns not one, but two (!) Honus Wagner T206 cards. One of them was pasted to a piece of paper a long time ago, and each time I see that one I want to scream. What a waste!

But I digress. This library is better, but worse. They are on guard for all things liquid, so my iced coffee resides behind the reference desk. The guy next to me has his in his cubicle with him, but I won't turn him in. Not that kind of guy. But they wouldn't even let me put it on the big table behind me. I'm clearly over it. These cubicles, though, are very cool because they have three plugs built into the left corner of each one, so I don't have to trail my Mac's cord across a room to plug it in. My cubicle seems to be the main one, too, because there is also a large surge protector beneath it, in case I had 27 more things to plug in. This cubicle also has a shelf just above those plugs, and the desk of the cubicle itself is big, so that the whole situation is very convenient. Nice!

I also noticed that there are a ton of books about the Middle Ages, and even some that are encyclopedias of everyday life of various eras. How cool is that?!? So I know where to come and research for the chapters of the past for my plague novel (research for much of it you will find in previous blog posts, below). This area is also relatively quiet, especially now that the buffaloes behind me are gone. They had been playing loud games on the library computers and, after pausing, talking loudly about them, like they were in their 80s and wearing hearing aids. Why didn't the coffee police speak to them? Never mind, I'm over it. Clearly.

The paper is going well. I found a story by Chekhov and one by Munro that both contain the following things: remote location (this works literally and figuratively); thoughtful and reflective characters; a sudden kiss by an unexpected person; epiphanies caused by the kiss; a bridge at the end (also effective for literal and figurative purposes--and structural ones, too); minor characters who do not think or reflect as often or as deeply; minor characters who do not seem to suffer--or to be as aware--because of this; and overall examples of the everyday and their ordinary characters' responses to these everyday things. I have so much, in fact, to comment on, and to cite, that I might not have the space for a Carver comparison after all. Fine with me. We'll see.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

Chekhov, Munro and Carver

I haven't posted in a few days. Working hard on my latest paper for the present grad. class, and besides I've been just plain exhausted. I even took a nap at home after work the last few days, which is not common for me.

So, this paper. I've decided to show the similarities between Chekhov, Munro and Carver, since the latter two are often compared to the first. Munro was famously called "our Chekhov" by fellow writer--and Canadian--Cynthia Ozick, and Carver wrote a short story about the last moments of Chekhov, who was a favorite of Carver's. Carver spoke of him exhaustively.

This paper will start with several quotes of people who compare Munro and Carver to Chekhov, because of structural and textual reasons. Then I begin the comparisons themselves by comparing Chekhov's "The Kiss" to Munro's "Floating Bridge." I do this because both stories are structurally similar. They're both essentially plotless--things just kinda happen. Then there's the primary image, for which both stories are titled. Both end with the characters standing on a bridge, both literally and metaphorically. In Chekhov, this bridge is, of course, one of despair; in Munro, it is, of course, of a hopeful epiphany. It'd be wonderful if I could also do this for one of Carver's stories, but for now a similar story with this many similarities escapes me. But I checked out his Complete Stories, so I hope to find one.

I have decided all of this today. This paper is due Tuesday at 4pm, and I have to work Monday and Tuesday, so I basically have tonight, all day and night tomorrow, and then Monday night, to type the whole thing. Final product must be 12-15 pages, MLA, all that. Wish me luck!!!

So, this paper. I've decided to show the similarities between Chekhov, Munro and Carver, since the latter two are often compared to the first. Munro was famously called "our Chekhov" by fellow writer--and Canadian--Cynthia Ozick, and Carver wrote a short story about the last moments of Chekhov, who was a favorite of Carver's. Carver spoke of him exhaustively.

This paper will start with several quotes of people who compare Munro and Carver to Chekhov, because of structural and textual reasons. Then I begin the comparisons themselves by comparing Chekhov's "The Kiss" to Munro's "Floating Bridge." I do this because both stories are structurally similar. They're both essentially plotless--things just kinda happen. Then there's the primary image, for which both stories are titled. Both end with the characters standing on a bridge, both literally and metaphorically. In Chekhov, this bridge is, of course, one of despair; in Munro, it is, of course, of a hopeful epiphany. It'd be wonderful if I could also do this for one of Carver's stories, but for now a similar story with this many similarities escapes me. But I checked out his Complete Stories, so I hope to find one.

I have decided all of this today. This paper is due Tuesday at 4pm, and I have to work Monday and Tuesday, so I basically have tonight, all day and night tomorrow, and then Monday night, to type the whole thing. Final product must be 12-15 pages, MLA, all that. Wish me luck!!!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)