Showing posts with label Europe. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Europe. Show all posts

Sunday, November 5, 2017

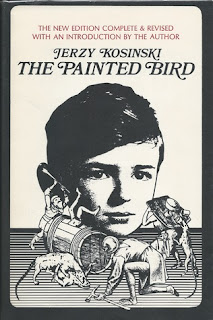

The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosinski

Photo: hardcover from the book's Goodreads page

Oh. My. God.

There's really no other way to review it. What can you say? It's impossible for one little boy to have been through all this and to survive this, so I'm compelled to agree with the consensus that this is not autobiography, not even biography, and Kosinski was indeed a fraud for saying so.

But like most of James Frey's A Million Little Pieces, so much of this could be true, especially (again like Frey's book) in character composite, that it feels true, rings true, and--understood as allegory--certainly reads true. No little boy could possibly be beaten this many times, so savagely, or have seen so much brutality and savagery, so many murders and rapes by every type of person...No little boy can live the life of a Hieronymous Bosch painting and survive it, physically or mentally.

And yet people did. As a mirror to the Holocaust, this rings remarkably and horrifyingly true. And people survived this brutal murder-and-rape life in the Middle Ages, too--Reading this was like reading Barbara Tuchman's A Distant Mirror, picked up and plopped into Eastern Europe, 1939-1945. Really, that's a good comparison: a lot of Bosch, a lot of the Holocaust and a lot of the brutal Middle Ages, all stirred together.

It doesn't matter to me who wrote this--and it's pretty clear, I guess, that Kosinski didn't. If he did, he wrote it in Polish and it was translated. It doesn't matter. It exists, and the writing is staggeringly uniform. There are maybe twelve lines of dialogue in all its pages. The sentences are simple and detached, with a smattering of social observance thrown in, especially when detailing the trains bringing the Holocaust's victims to the camps. Someone wrote it, and it's important that someone did. This is a book that serious readers should read--and don't feel guilty if you can't make your way through it all. It is brutal. But has someone lived like this? Yes. A great many, sadly. And a great many animals have lived like this, too.

It is as brutal a look at humanity as you will likely see. And it is not untrue in of itself, even if it was for Kosinski personally. It is unflinching and unsparing. It will make you grateful for your days, for your loved ones, for life itself. You will maybe be more empathetic. This book, like all great literature, could change your outlook of the world, of people. It may, it may not, but it could, and that's rare in literature, in movies, in any segment of real life. For this it should be read and reveled.

Labels:

1939,

1945,

A Distant Mirror,

A Million Little Pieces,

bird,

book,

Bosch,

Europe,

goodreads,

Holocaust,

James Frey,

Jerzy Kosinski,

literature,

Middle Ages,

movie,

murder,

painting,

rape,

The Painted Bird,

Tuchman

Thursday, September 8, 2016

Death and the Maiden -- A Very, Very Short Review

Photo: From the book's Goodreads page. Not my exact edition, but this one has the same number of pages, and the one on Goodreads that looked like mine had more pages. Weird. And I didn't want my stats to show that I've read more pages than I actually have. I take my Goodreads stats very seriously!

Very satisfying 6th--and perhaps final--Max Liebermann mystery, written by Frank Tallis. Published in 2012, and followed by okay horror novels in the last few years, all published as F.R. Tallis, for some reason, this is perhaps Liebermann's last go. If so, it's a shame, as this series is clearly Tallis's best writing, and is what he's known for--if he's known in the U.S. at all; he's more popular, I think, in Europe. At any rate, he said in an interview that he was worried of his characters and plots becoming stale, and that he'd become tired of the series. So be it, I suppose.

This one has all of the good stuff you expect in this series: the locales, the detail of 1903 Vienna; Freud; a beautiful woman murdered (though let the record show that literally every woman worthy of mention in the series has been beautiful, especially the murdered ones); Amelia, who has been underwritten and under-represented; and of course Rheinhardt. The extra touch of this one is the appearance of Gustav Mahler, famous composer and conductor, often referenced in the series but never seen. We see Clara again, too; I have begun to feel quite badly for her now. Not a bad person, and probably deservant of more happiness than she's allowed. Her reason for wanting to be with Liebermann again was a little depressing, as was the reason for her final departure. She'll end up with that soldier, and she'll never be wanting, but you get the feeling she'll never be happy, either.

The book ends on a note that rings true, though not one that will give closure to every reader. Like the characters, you have to sometimes shrug your shoulders in life and accept the path that lays before you. Stray from that path at your peril--or, at the peril of your family. See: No Country for Old Men, by Cormac McCarthy. The movie lives up to the grueling realism of the book. Overall a very good book, but hopefully not the end to the series. Again, we'll have to shrug and move on if that's the case, but let's hope it's not.

Labels:

1903,

2012,

Amelia,

beautiful woman,

book,

Clara,

composer,

conductor,

Cormac McCarthy,

Europe,

Frank Tallis,

Freud,

Gustav Mahler,

Max Liebermann,

movie,

murder,

mystery,

No Country for Old Men,

U.S.,

Vienna

Thursday, January 7, 2016

In the Wake of the Plague -- The Black Death and the World It Made

Photo: A Bubonic Plague map, from the Wikipedia page The Black Death in England. This site quotes that up to half of England's population died of the plague in the Middle Ages, and another 20% later--and that doesn't count the last epidemic, the The Great Plague of 1666.

Fascinatingly in-depth, yet quick-to-read, take on everything Black Death. This includes, but is not limited to:

--the biomedical facts of the Plague. The memorable kicker here is that scientists have concluded, by digging up bodies of Plague victims in the frozen Arctic, that the Great Pestilence may have made about 10%-15% of today's descendants of Plague survivors immune to HIV, which causes AIDS. This would've been certain by now, since the completion of the Human Genome Project, as this book was published in 2001. The other memorable factoid is that anthrax was most likely killing off Europeans--especially the British--as the Plague was doing so as well, making London of the Middle Ages the worst place to be of all-time. This explains why millions died in the winter--when rats and fleas are not abundant--and why millions died in the Frozen Arctic, where rats and fleas don't go at all. Turns out, many of those people didn't die from the Plague--they died from anthrax. And, why didn't many people have the tell-tale buboes and skin and blood lesions that Plague victims got? And why did some people get struck by the virus one night and die before morning, which was unusual for Plague, which took days or weeks? Answer, again: anthrax.

--social and economic aftereffects of the Plague. In short, yeomen and women flourished, economically. The Church was devastated and hired younger and more undereducated people, as the older but learned leaders died off. Serfdom ended. People questioned the infallibility of their monarchies (who were supposedly God-chosen and God-protected, but who during the Plague were God-forsaken) and of the Church, and of medicine. After all, if the priests and friars and physicians couldn't save themselves, how could they save (spiritually and medically) anyone else? And if they couldn't do that, what good were they at all?

--artistic expression. Commonly thought to have become more morbid and pessimistic after the Plague, Cantor believes that art was going that way anyway, and that Renaissance art was less of a mirror of the Plague than previously thought. I'm surprised by this, but Cantor is hugely respected, and he quotes many others, so I'll take his word for it.

--world government. The Plague spelled the end for the Plantagenets, which was a long-lasting monarchy and European power that you and I have never heard of. But they would've ruled England and Spain, and maybe, by default, France, at the time, which was a constant thought of every monarch for hundreds of years, but would've actually happened. But English Princess Joan, who was about to marry into the Spanish monarchy, died of the Plague (in France, at 15), and so that never happened. This led to the trials and tribulations of Edward II and III, and of Henry IV-VI, and, well, the rest is history.

--medical and scientific stagnation. These two things were just as much to blame as were the actual Plague and anthrax, as the vacuum of medical and scientific advancement in the Middle Ages (except in the field of optics) made these pandemics worse, and longer-lasting, than they necessarily had to be. Nobody knew or practiced anything that could've combated the Plague, so the main response was to pray, flee and blame--

--the Jews. The Plague wasn't the first time they were scapegoated, but perhaps this was the first European-wide excuse to massacre them, as entire villages, households and neighborhoods of Jews were set aflame and otherwise wiped out because the common man thought they were poisoning the wells, thereby creating and spreading the Plague. The first of many Jewish holocausts over the years.

In short, if you're interested at all in the Middle Ages, in the Renaissance, or in the Plague, this is necessary reading. An informative, well-written (and often sarcastic) account of the Plague, the people and the time.

Thursday, October 1, 2015

New Disasters--The Black Death

Interesting little book--just 111 pages--about the Black Death of the Middle Ages, between 1347-1351. I saw it in my local library while I was researching plagues and flus for my next novel. Though I'm focusing more on the Great Plague of the 1660s in England, and not the Black Death of the Middle Ages (for they're not the same thing, and there are a great number of differences), I figured I could learn a little something from this.

It's broken up in sections: its arrival; recent scientific re-assessments (this was published in 2003, so it's still relatively recent); writings about the plague from the time; and the repercussions of the Black Death.

What I learned, in no particular order:

--It seems now rather certain that the Black Death wasn't just the Justinian Plague, carried by fleas on black rats. Lots of evidence indicates that anthrax (the disease that killed cattle, not the powdery stuff used in germ warfare today) was also going around, either on its own or as a unique anthrax / plague strain.

--Part of the evidence for this was the unbelievable number of animals dying before the people started to die. Also, the deaths did not abate much in the winter--odd for a plague dependent on fleas and rats to spread it. (Neither survive or move around much in the winter.) And people died with extreme rapidity from a third strain of the plague; it was said that they could go to bed feeling fine and be dead by morning. (This does not seem to be an exaggeration.)

--The plague was said to come from vapors within the Earth, released during earthquakes. It was believed that breathing man-made yuckiness--like from latrines--was beneficial, and would fight off the nastiness from within the Earth. Planet alignments and other astrological things were also blamed.

--People died faster than they could be buried. Putrefying bodies of people and animals would lie in the streets, and the stink was said to be incredible.

--Gravediggers, doctors and clergy died fastest, as they attended to the dead and dying. Since nobody was left alive to bury the dead--and since those left alive didn't want to touch the dead or dying for fear of getting sick from their "humours" and "vapors"--a lot of money was paid to people who called themselves becchini. These people would take the dead from their homes, from the streets, etc. and bury them. But after awhile, nobody wanted to touch or associate themselves with these people, either, so the becchini became disgruntled and homeless, and often turned to crime.

--Those who couldn't afford to be cared for or buried simply weren't, and died alone in horrible conditions, and their bodies left to rot wherever they died.

--The Black Death may have some DNA in common with the HIV / AIDS virus. Recent evidence suggests that 12%-15% of those with European descent--and an ancestor who contracted the plague and survived it--may be immune to the HIV / AIDS virus as well as the Black Death.

--The same plague from the Middle Ages is alive and well in a few spots, including the Midwestern U.S. Some cases have cropped up in Colorado recently.

--A strain of the Plague--as well as strains of other viruses--are immune to today's strongest antibiotics. A cocktail of super-antibiotics is used to fight these resistant viruses now. Once the viruses become immune to these cocktails--which is very soon--there won't be anything left to stop them.

--God, then like today, was thought to be punishing the bad people. [See: AIDS in the 80s.] But then everyone, of every stripe, class, age and religion, started dying, so that theory was dashed by everyone--except the living, of course, whose every breath proved their moral superiority.

--A common "cure" was to bleed and purge the victim. This led to an even more rapid death due to blood loss, exhaustion, dehydration, and a weakened immune system. Those who came in contact with the blood or feces of the victim could contract the illness as well, so that the "cure" killed them, too.

--Mercury was often recommended, which made plague victims die of the plague and of mercury poisoning. Several learned people complained that their doctors were killing them quicker than the pestilence was. (BTW, the plague was never called the plague at the time. It was called a "pestilence" or "the Great Pestilence.")

--The most common thing doctors did for the victim? Study their urine.

--In some towns, when one member of a family got sick, the entire family was sealed inside the home, so that everyone--the healthy and the sick--died.

--Before everyone died of the plague, those blamed for it the most were the Jews and the undesirables of society. [See: World War II.] It was commonly believed that Jews were poisoning the wells, and tens of thousands of Jews across Europe were hunted down because of this belief, including entire communities.

Anyway, a little book that, in these virus-ravaged days, makes for some eye-opening, if not chilling, reading. With the Earth long overdue for a pandemic like the 1918 super-flu, and with our current attitudes about change and blame, this book made for some quick, interesting and thought-provoking reading.

The more things change, it seems, the more things stay the same.

It's broken up in sections: its arrival; recent scientific re-assessments (this was published in 2003, so it's still relatively recent); writings about the plague from the time; and the repercussions of the Black Death.

What I learned, in no particular order:

--It seems now rather certain that the Black Death wasn't just the Justinian Plague, carried by fleas on black rats. Lots of evidence indicates that anthrax (the disease that killed cattle, not the powdery stuff used in germ warfare today) was also going around, either on its own or as a unique anthrax / plague strain.

--Part of the evidence for this was the unbelievable number of animals dying before the people started to die. Also, the deaths did not abate much in the winter--odd for a plague dependent on fleas and rats to spread it. (Neither survive or move around much in the winter.) And people died with extreme rapidity from a third strain of the plague; it was said that they could go to bed feeling fine and be dead by morning. (This does not seem to be an exaggeration.)

--The plague was said to come from vapors within the Earth, released during earthquakes. It was believed that breathing man-made yuckiness--like from latrines--was beneficial, and would fight off the nastiness from within the Earth. Planet alignments and other astrological things were also blamed.

--People died faster than they could be buried. Putrefying bodies of people and animals would lie in the streets, and the stink was said to be incredible.

--Gravediggers, doctors and clergy died fastest, as they attended to the dead and dying. Since nobody was left alive to bury the dead--and since those left alive didn't want to touch the dead or dying for fear of getting sick from their "humours" and "vapors"--a lot of money was paid to people who called themselves becchini. These people would take the dead from their homes, from the streets, etc. and bury them. But after awhile, nobody wanted to touch or associate themselves with these people, either, so the becchini became disgruntled and homeless, and often turned to crime.

--Those who couldn't afford to be cared for or buried simply weren't, and died alone in horrible conditions, and their bodies left to rot wherever they died.

--The Black Death may have some DNA in common with the HIV / AIDS virus. Recent evidence suggests that 12%-15% of those with European descent--and an ancestor who contracted the plague and survived it--may be immune to the HIV / AIDS virus as well as the Black Death.

--The same plague from the Middle Ages is alive and well in a few spots, including the Midwestern U.S. Some cases have cropped up in Colorado recently.

--A strain of the Plague--as well as strains of other viruses--are immune to today's strongest antibiotics. A cocktail of super-antibiotics is used to fight these resistant viruses now. Once the viruses become immune to these cocktails--which is very soon--there won't be anything left to stop them.

--God, then like today, was thought to be punishing the bad people. [See: AIDS in the 80s.] But then everyone, of every stripe, class, age and religion, started dying, so that theory was dashed by everyone--except the living, of course, whose every breath proved their moral superiority.

--A common "cure" was to bleed and purge the victim. This led to an even more rapid death due to blood loss, exhaustion, dehydration, and a weakened immune system. Those who came in contact with the blood or feces of the victim could contract the illness as well, so that the "cure" killed them, too.

--Mercury was often recommended, which made plague victims die of the plague and of mercury poisoning. Several learned people complained that their doctors were killing them quicker than the pestilence was. (BTW, the plague was never called the plague at the time. It was called a "pestilence" or "the Great Pestilence.")

--The most common thing doctors did for the victim? Study their urine.

--In some towns, when one member of a family got sick, the entire family was sealed inside the home, so that everyone--the healthy and the sick--died.

--Before everyone died of the plague, those blamed for it the most were the Jews and the undesirables of society. [See: World War II.] It was commonly believed that Jews were poisoning the wells, and tens of thousands of Jews across Europe were hunted down because of this belief, including entire communities.

Anyway, a little book that, in these virus-ravaged days, makes for some eye-opening, if not chilling, reading. With the Earth long overdue for a pandemic like the 1918 super-flu, and with our current attitudes about change and blame, this book made for some quick, interesting and thought-provoking reading.

The more things change, it seems, the more things stay the same.

Labels:

AIDS,

anthrax,

black,

Black Death,

blood,

Death,

doctor,

Earth,

England,

epidemic,

Europe,

flu,

God,

HIV,

Jew,

Middle Ages,

plague,

poison,

rat,

World War II

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Marathon Bombing

Photo: Boston's finest rushing to help an injured runner. This will be SI's cover. From mashable.com.

My thoughts, such as they are, on this week's marathon massacre and the FBI's and Watertown PD's amazing capture of Suspect #2. There'll be another post soon that chronicles my thoughts as the week unfolded:

--This week's news reporting was the best of up-close and immediate news and technology. And the worst. It was the best because we were up-to-date about a really serious issue--this was news worth the attention, for once. But we were in people's backyards. Reporters and cameramen had to be told by the police and FBI to not report on tactical information, to not show how they were about to storm the boat, to constantly get back. Incorrect information was reported around the world before it was checked by reporters. For example, the supposed post of "You killed my brother, now all of you will die," or something like that, was incorrectly reported as written by the second suspect. Instead, it was written by some loser hoaxer. And a student missing for a long time now from Brown University was reported as one of the suspects. He wasn't, and he's still missing. The positives far outweighed the negatives, but as this sort of coverage happens more and more, I hope news stations don't get more powerful, more arrogant, more resistant to the authorities and to responsible and accurate reporting.

--Before the post-bombing events unfolded, I made a sort of criminal profiling blog that I didn't post, because I thought it'd be a disservice to those who suffered, and, also, frankly because I thought I'd be so wrong that I'd embarrass myself. (Back during the DC Sniper situation, I wrote a long email to a friend that was my attempt to amateur profile the situation. I was right about most of it, including that there were two snipers, that one was much older than the other, that they were living in a vehicle, and even about their race and approximate ages. I was wrong about the vehicle: I predicted a van, but they were in a Chevy Caprice, with a hole in the trunk's lock for the gun barrel. There will always be some sort of anomaly.) This sort of thing is more playing the odds, more common sense, than any sort of talent or intelligence. Anyway, here's what I'd thought, and what actually happened:

--I thought there'd be two of them, maybe more, if the information was correct about the JFK Library's fire (it wasn't) and if there were two other bombs that didn't detonate (there weren't). I thought that, if there were two, they'd be very close (but I didn't anticipate literal brothers), and that there'd be an age gap (but I predicted a larger gap, like with the two DC snipers). I never thought there'd be just one, someone who planted the bombs himself and detonated them separately on a timer. I thought this because, if there had been just one, it'd make more sense for him to detonate them at exactly the same time, because people will run away from the whole race once the first bomb explodes.

--I thought the suspects would be younger, both in their teens and/or twenties, but younger than thirty. And that, along the same lines, I thought they'd be students at one of the great many nearby universities. (I thought these because--Why the marathon? It struck me as an odd thing to terrorize. My conclusion is that the suspects must've been very familiar with it. Why's that? Because they're nearby.) I thought they'd be wearing caps or hoods. This last is a minor thing, but not everyone wears caps and/or hoods, and the authorities would need something to exclude some of the people they'd have to analyze on film or in photos. And the suspects would know there'd be cameras somewhere--though that's what ultimately caught them, anyway. Turns out, in an urban area, there are cameras everywhere.

--But I thought there'd be a much more personal reason for the bombings, something not completely political or religious. I was totally off-base about that, which is why I'm just an amateur at this. The suspects purposely bombed the onlookers, most of whom would be American. And they bombed the Boston Marathon itself.

--I thought the suspects would have more of a personal reason because the bombs went off long after the professional--and, often, international--runners had finished, so I thought they wouldn't be the targets. And if the professional, international runners weren't the targets, then the amateur runners must have been. Turns out, there are a lot of international amateurs who run in the marathon (for some reason, my thinking was limited on this). And it now seems like the crowds themselves were the targets, not any of the runners.

--However, I was on about their approximate nationalities, based on the pressure-cooker, which has been a sort of specialty used in conflicts in many Eastern-European, Russian-bloc countries. As well as in conflicts in some countries where every type of bomb has been used. I thought the suspects would not obviously stand out in appearance, so that they'd probably "look American," whatever the hell that means.

--I thought the FBI should release the images of the suspects, which national intelligence organizations are often reluctant to do. Once they did, it was all over in about twenty-four hours. But the rapidity of that shocked me, as it did everyone else.

--I thought it might have been possible for the suspects to be tied into the specific restaurant or whatever that the bombs were placed in front of. Totally wrong on that.

Well, that's about it, as far as that kind of thing goes. Next time I'll post something about my thoughts during the week as everything unfolded.

I want to close by saying that I will not soon forget the horror I felt during the initial event, and the respect and admiration (words I do not throw around, and emotions I do not quickly and easily feel) for the men and women who helped the victims and who fought and apprehended the suspects.

For many of them, law enforcement is a personality, not just a job.

People are inherently good, and many of them are inherently good at what they do.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)